Monte Claro

Nuragic pottery from Monte Claro

Cagliari’s origins are lost in the mists of time, and cannot be attributed to one civilization. The first reported human settlements belong to the prehistoric era, and they were spread out over a large area, suggesting that this was not one compact nucleus, but rather a collection of sites. The excavations made on the hill of Monte Claro have brought to light remains of the progression of a civilization between 1700 and 1550 B.C. This was known as the ‘nuragic civilization‘.

In the beginning of the 10th and 11th century B.C., Phoenicians began to use the gulf of Cagliari as a landing point. They truly settled here in the 8th century, when they began to make homes on the promontory of Sant’Elia and the lagoon of Saint Gilla. According to several scholars the etymological roots of Cagliari are probably derived from this group of people: Karel, a Phoenician word, means ‘city of God‘, or ‘large city‘; ancient sources record the name in the plural, i.e. Karales, written in other documents as Calares. Votive phoenician pottery, in hellenistic style but locally produced, dating from the 4th-3rd century BC, were found in the Santa Gilla marsh.

Lagoon of Saint Gilla

Votive phoenician pottery from Saint Gilla

However, Cagliari could still not be called a city in terms of being an urban center. This significant change could only have taken place when the Carthaginians arrived in the 6th century who slowly gave this area a more urban look and feel, rather than the discontinuous, casual settlements that were there before. Religious buildings were constructed along with homes, necropoli, and water cisterns. The city was extended along the coast from the hills of Bonaria, until the area which today hosts the quartiere of Sant’Avendrace.

Monumental Cemetery of Bonaria

Necropolis of Tuvixeddu

Cagliari was blessed with agricultural produce from Campidano but also with a local production of salt, the city was set to become a center of activity with an intense commercial life. It was linked by sea to Tunisia, as well as France and Spain, it was also under punic control. There are many indelible signs of their work and activities. Traces of the religious life are visible in the terracotta votives of Santa Gilla, in the Necropolis of Tuvixeddu, in the Temples of Via Malta, Monumental Cemetery of Bonaria, and in the Tophet that stands in San Paolo, also in the military votives in the walls and towers.

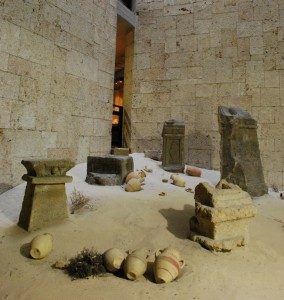

Tophet in San Paolo church

The fact that the Carthagians preferred to move around the plains leads to the assumption that the Castle was not used as a real acropolis at that time.

The Roman amphitheatre of Cagliari

The city moved to Roman hands in 238 B.C., but it still reserved all of its attributes as a commercial center. Rome, like Carthage preferred the planes to the hills or the gentle slopes, favouring a development of the city, which was lengthwise without moving too much inland. This did not prevent roads from linking the city with other cities such as Tibula (nowadays known as Santa Teresa di Gallura) or Olbia, Porto Torres, encouraging not only commercial activities, but also the movement of legions who were employed to oppose the autonomous resistance of the inland such as Barbagia. In 46 B.C. Cagliari, the ‘barn of Rome’ and the capital of Sardinia, hosted Julius Caesar, who erected the municipium, giving it a great deal of importance. Rome made Cagliari a city of high rank; it had many paved roads acqueducts, sewers, thermal baths but there were also many prestigious buildings such as the magnificent Anfiteatro built in the II century AD or the Villa di Tigellio dating back to the period between the era of Augustus and the 4th century AD and the area of Marina was transformed into a fortress. There are several other important constructions, as for example the Viper’s Cave, near the Punic necropolis, a mausoleum tomb dedicated to Attilia Pomptilla built by her husband, Philip Cassio. It is decorated with an impressive cycle of Greek and Latin CARMINA that can be considered the first literary work produced in Sardinia and surviving to the present day, the beginning of the literary history of the island.

Botanic Garden

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Sardinia was under the dominion of the Vandals from 455 to 533 and Cagliari was the place of exile and deportation. The Byzantines came next, but their government and their administration was not well tolerated, which helped the arrival of the Goths (552) who lost control of it in 578 when the Byzantines took possession once again. More significant traces of the Byzantine dominium were found in the area which today houses the Botanic Garden, in the San Michael church , where the Orthodox religion was practiced, and the Basilica di San Saturno. This was the long period of peace, during which time the city of Cagliari became the center for the spread of Christianity.

San Michele Castle

In the year 753 AD, Arab sources report the imposition of the Jizya, a tax for those not converted to Islam, on the Sardinians. This presumes the occupation of the land on which it is imposed, but the lack of further sources suggests ephemeral occupation and control confined to some coastal regions. On this occasion, however, the Arabs could have imposed the dismantling of the defenses of the city. When in 827 the Arabs began their conquest of Sicily, contacts with Constantinople became extremely difficult. The few available sources suggest that the richest and most influential family of the island began to take over the local government. This state—although a vassal of the Byzantines—was in fact independent. Cagliari became the capital of this independent kingdom or giudicato, ruled by a judice (literally “judge” or magistrate). However, there is some evidence that during this period of independence from external rule the city was reduced to a small port community because it was too exposed to attacks from the sea by Moorish pirates (Mori). Apparently many people left Caralis and founded a new town (named Santa Igia) in an area close to the Santa Gilla swamp to the west of Cagliari, but relatively distant from the sea. At the present state of research, the site of historic Santa Gilla has not yet been identified, because it was completely destroyed by the Pisans in the thirteenth century. The walls were dismantled, as well as the cathedral and the palace of the judice. San Michele Castle, located on one of the highest hills of Cagliari, is from “Giudicale” Period (tenth century AD) and it had the defensive function of Santa Igia, the capital of the “Giudicato” of Cagliari. After the failed attempt at conquest of Sardinia by the Spanish in about 1016, the kingdom was divided into four judicati, one of which was named Callaris, in reference to its capital, now modern Cagliari. The Judicatus of Cagliari comprised a large area of the Campidano plain, the mineral resources of the Sulcis region, and the mountain region of Ogliastra. There were three other independent and autonomous giudicati in Sardinia: the Logudoro (or Torres) in the northwest, the Gallura in the northeast, and in the east the most famous, the long-lived Giudicato of Arborea, with Oristano as its capital.

Torre e Porta dell’Elefante (Elephant Tower and Gate)

Porta del Leone (Lion Gate)

During the 11th century, the Republic of Pisa began to extend its political influence over the Giudicato of Cagliari. Pisa and the maritime republic of Genoa had a keen interest in Sardinia because it was a perfect strategic base for controlling the commercial routes between Italy and North Africa. In 1215 the Pisan Lamberto Visconti, giudice of Gallura, obtained by force the mountain located east of Santa Igia. Soon (1216/1217) Pisan merchants founded on this mount a new fortified city to be known as “Castel di Castro“, which can be considered the ancestor of the modern city of Cagliari. Some of the fortifications that still surround the current district of Castello (Casteddu ‘e susu in the Sardinian language) were built by the Pisans, most notably the two remaining white limestone towers designed by the architect Giovanni Capula (originally there were three towers guarding the three gates that gave access to the district: Porta del Leone (Lion Gate), Porta dell’Elefante (Elephant Gate) and Porta San Pancrazio (San Pancrazio Gate): Torre di San Pancrazio (San Pancrazio Tower) and Torre dell’Elefante (Elephant Tower). Together with the district of Castello, Castel di Castro comprised the districts of Marina (which included the port) and the later Stampace and Villanova. Marina and Stampace were guarded by walls, while Villanova, which mainly hosted peasants, was not. With the arrival of the Pisans, Cagliari became one of the most splendid examples of military architecture of the Medieval Age.

In 1324 the Kingdom of Aragon conquered Cagliari (Castel di Castro) after a battle against the Pisans. When Sardinia was finally conquered by the Catalan-Aragonese army, Cagliari became the administrative capital of the newborn Kingdom of Sardinia, one of the many kingdoms forming the Crown of Aragon. Since 1326, the city, having expelled the Pisans and been repopulated by Catalans, Valencians and Aragonese, began a new period of development, soon interrupted by the war between the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Judicatus of Arborea. The war lasted, with ups and downs, from the mid-14th century to 1420, with the Judicatus full debellatio. During this long period, the city, along with the city of Alghero, was often the Aragonese monarchs’ only garrison on the island and it never fell into the hands of Arborences. The kings of Aragon, and later the kings of Spain (who were also Kings of Sardinia), were represented in Cagliari by a viceroy. The city was enclosed in strong fortifications and its architecture was oriented towards the late Catalan Gothic style.

In 1479, after the union of the crowns of Castalia and Aragon, the Castilians reached Sardinia and the whole of Sardinia were bound more and more to the nascent Spanish state. The Catalan language was the official language of the Cortes of the Kingdom, but its active use gradually died out in the city, overwhelmed by Sardinian in everyday use in every social class, even in the nobility, and it was replaced by Spanish as the language of culture and government. The city remained the capital of the kingdom and the most wealthy and populous city, with its status of royal and autonomous city. Besides being the main export centre for Sardinian goods, its port was an inevitable staging point in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean routes to the Iberian peninsula. It was equipped with a powerful defense system of ramparts and bastions, which transformed it into the key stronghold for controlling the western Mediterranean.

Feast of Sant’Efisio

In 1607 the University was established, as was the first public hospital. But the decadence that the Spanish Empire experienced in the second half of the seventeenth century also damaged the city and exposed it to a serious outbreak of plague in 1656, from which came by municipal vow the Feast of Sant’Efisio, still the most important religious event of the island.

In 1718, after the brief rule of the Austrian Habsburgs, the Savoy dynasty obtained the Kingdom of Sardinia, which remained an autonomous institution in relation to the mainland states of the dynasty and solemnly swore to respect the ancient customs and privileges. But the eighteenth century was the era of absolute monarchies, and the new ruling house gradually transformed the old kingdom created by the medieval Aragonese kings into one best suited to the needs of the new times. For half a century Spanish remained the official language. The formal capital was Cagliari, but now all decisions were made at the court of Turin, residence of the monarchs. Nevertheless, the city slowly grew and benefitted from the Age of Enlightenment, with the reorganization of the university, the strengthening of the defense system, the restructuring of the Royal Palace, and access to the markets of central and northern Italy and Europe.

In the late 18th century during the Napoleonic wars France tried to conquer Cagliari because of its strategic role in the Mediterranean Sea. A French army landed on Poetto Beach and advanced towards Cagliari, but was defeated by Sardinians who defended themselves against the revolutionary army. People from Cagliari hoped to receive some concession from the Savoys in return for their defense of the town. For example, aristocrats from Cagliari asked for a Sardinian representative in the parliament of the kingdom. When the Savoys refused any concession to the Sardinians, inhabitants of Cagliari rose up against the Savoys and expelled all representatives of the kingdom and people from Piedmont. This insurgence is celebrated in Cagliari during the “Die de sa Sardigna” (Sardinian Day) on the 28th of April. However, the Savoys regained control of the town after a brief period of autonomous rule.

City Hall

Bastione of St. Remy

From the 1870s, with the unification of Italy, the city experienced a century of rapid growth. The ancient medieval and 16th century walls were dismantled, wide avenues were opened and a rational urban plan was designed. Many outstanding buildings were erected by the end of the 19th century combining influences from Art Nouveau together with the traditional Sardinian taste for floral decoration; examples are the white marble City Hall near the port and Triumphal Arch King Umberto I, better known as the Bastione of St Remy. In 1871 the first stretch of railway to connect Cagliari to Sassari and Porto Torres was inaugurated. The project was completed in 1881. In 1893 a suburban steam tram service was started, connecting the city center with the towns that are now part of the metropolitan area, Monserrato, Selargius, Quartucciu, and Quartu Sant’Elena. In 1913 another steam tram line connected downtown with Poetto Beach. In 1915 the first two electric urban tram lines were inaugurated.

Tribunal Palace

Carabinieri brigade commander palace

During the Fascist period the city experienced rapid population and economic growth and a monumental building policy inspired by the ideology of the regime. Fascist architecture and urbanism, such as the tribunal palace and the Carabinieri brigade commander palace, still constitute the main reference points of the modern city.

During World War II Cagliari was heavily bombed by the Allies in February 1943. The fascist war caused the destruction or serious damage of 80% of the city’s housing and the death of almost 2,000 civilians, due mostly to cluster bombs. In order to escape the bombardments and the misery of the destroyed town, almost everyone left Cagliari and moved to the countryside or rural villages, often living with friends and relatives in overcrowded houses.

After the war, the population of Cagliari rebounded. The city was so quickly rebuilt that there was talk of the Cagliari miracle, and many apartment blocks were erected in new residential districts, often created with poor planning as to recreational areas.

Nowadays Cagliari is the hub of a modern metropolitan area of about half a million inhabitants, with a vibrant and differentiated economy, which makes it the largest and richest community of Sardinia with a standard of living equal to that of the cities of northern Italy and well away from the degradation of those in the south. In addition to being the center of administration of the Autonomous Region and peripheral administrations of the Italian State in Sardinia, it has a major port with a large container terminal, remarkable industrial development in particular with one of the largest oil refineries of Europe, a large university and research centers, high-standard medical facilities, a wide network of large and small commercial assets, a considerable amount of touristic traffic, and one of the most important Italian airports.